How we make bunko leather

Bunkoya Oozeki has used the same bunko leathermaking process for more than 90 years

Bunko leather is a type of handicraft that puts pure white leather through a unique processing technique.

This distinctive process gives our products a feel that you won’t find in any other type of handicraft. Naturally, every part of it is done by hand.

We start by embossing the white leather with a design (like an ukiyo-e print, traditional crest pattern, or flower pattern). We then color it by hand, brushstroke by brushstroke, before putting it through an antiquing process that makes use of Japanese lacquer. We then sew the wallet or accessory together to create the finished product. Our lacquer-based antiquing process is called sabi-ire. It also uses the powdered spores of a certain type of plant Makomo.

Sabi-ire antiquing is the secret to our bunko leather manufacturing process.

Long ago, there were many workshops that performed sabi-ire—but today, Bunkoya Oozeki is the only workshop of its kind left in Japan.

The careful handiwork of our artisans is what infuses our products with warmth and a personal touch.

Production

1. Cutting and embossing

White leather softened for use as bunko leather is cut to the right size for each item and then embossed with a pattern.

2. Coloration

Some of our coloration artisans work out of their own private workshops, while others are staff members who work out of our Mukojima workshop. Each one carefully applies color one brushstroke at a time.

3. Sabi-ire (antiquing)

The secret to bunko leatherwork is our unique antiquing process.

4. Finishing

The process continues with finishing to create a beautiful, durable leather product.

5. Finishing into wallets and accessories

Japanese sewing experts put together each piece individually.

About the wild rice we use

What is makomo wild rice?

Makomo is an essential part of creating bunko leather at Bunkoya Oozeki.

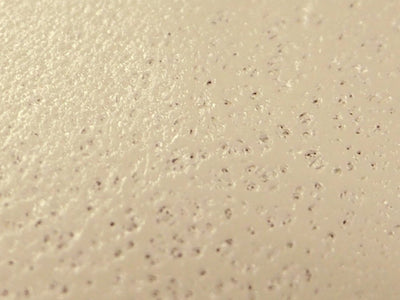

It’s a relatively uncommon kind of plant Makomo, but it is used to create the distinctive brown color you see outlining the recessed patterns in embossed bunko leather products.

Brown line drawing the pattern of paperback leather

About the makomo plant

The people of Asia have long used makomo wild rice as a food and in handicrafts. It has even been used in religious ceremonies as well.

The plant itself grows in clusters along lakes and riverbanks, typically reaching a height of 1–2 meters by August. It has been a familiar part of Japanese life since ancient times.

Zizania latifolia grows larger than a person's back

Is makomo rice making a comeback?

Despite its long history, the areas where makomo rice grows are slowly disappearing as lakeside marshes are filled in and natural riverbanks become increasingly scarce.

And it’s so easy to get rice straw these days (since it’s a byproduct of rice cultivation) that it’s actually made makomo rice harder to come by.

There is actually only one farming household left in Japan that grows makomo rice for handicrafts, and finding successors is a challenge.

It might appear that makomo rice is being slowly forgotten as the world moves on, but it is actually starting to gain renewed interest as a way to effectively enhance water quality around lakes and in other areas.

Its stems are now being sold in grocery stores as “wild rice shoots” and are gaining recognition as an ingredient in Chinese cuisine.

Zizania latifolia during dryingWild rice shoots as a food

Wild rice shoots are an important food crop throughout Asia—particularly in Taiwan and Vietnam. In Japan, they are more frequently being sold in Chinatown areas or at local roadside markets.

Because the shape and texture of wild rice shoots resembles bamboo shoots, it’s sometimes called makomo-dake when it’s used as a food ingredient in Japan.

The flavor and consistency is also similar to white asparagus or baby corn, making it delicious tempura-fried, stir-fried, or stewed. It’s also low in bitterness, so it can be eaten raw and is said to be good for detoxing.

MAKOMO POWDER

The makomo rice used to make bunko leather is actually not the plant itself, but a fine powder made from the spores of a type of smut fungus that lives in the leaf stems.

The leaf stems where the smut fungus takes hold become enlarged, so while that part of the rice plant can still be eaten while the plant is young, as the plant matures and the fungus spreads, it eventually produces more black pigment—killing the whole plant and turning it a rusty color.

The plant is no good to eat at that point, but if it is dried, the powdered fungus can be collected.

So makomo rice is the host for fine smut fungus spores that can be powdered to create nuanced shading in Japanese arts and handicrafts, which are known for their exquisite detail.

Zizania latifolia for crafts before drying

How makomo rice features in the bunko leather process

At Bunkoya Oozeki, we combine the makomo powder with lacquer, and then carefully rub it into the grooves in the embossed bunko leather. This is what creates the distinctive “antiquing” effect.

Bunkoya Oozeki’s proprietary techniques for mixing the wild rice and lacquer into a compound have been handed down at our workshop over the generations, so it’s only natural that we guard them very closely.

It is a painstaking process that requires the practiced hands of a skilled artisan. Everything must be just right—from the temperature and the humidity to the speed at which they work. The antiqued look and the warm outlines it creates are not effects that can be simply recreated with printed ink.

Craftsmanship dealing with lacquer and Zizania latifoliaCow leather

Cow leather is made from the skin of the animal

Most people think of cow leather—cowhide—as a highly durable material. But is it really?

Once skin is taken from the animal, it undergoes a tanning process in order to become leather. Only then is it used in the familiar applications we see every day.

Every kind of genuine leather was once the same type of cowhide, whether it’s the hard leather used in the soles of shoes or the soft leather used to make jackets. Each application requires a different level of hardness or flexibility, which is determined by the type of tanning process used.

Cows are obviously mammals, so they have fur and sometimes injure their skin. Leather was originally covering their three-dimensional shape. The reason it’s flat like woven fabric is because it’s been processed during tanning to make it easier for humans to use.

Bunkoya Oozeki has worked with tanners to develop just the right leather to create bunko leather, the kind of leather used in our generations-old manufacturing methods. We use a “white leather” designed just for us.

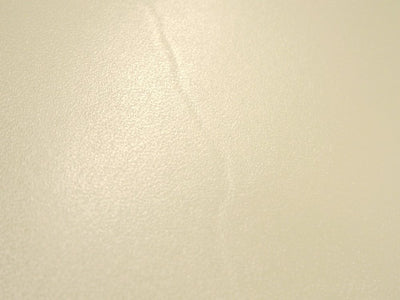

Characteristics of cow leather

We purchase cow leather in pieces that are half the size of the animal.

A cow leather half. The neck is on the upper left, the rear on the upper right, and the legs on the bottom left and right.

The pieces are large, but just like people, cows have scars, discoloration, wrinkles, moles, and pores on their skin.

The different parts of the body also have different characteristics. The texture, thickness, flexibility, or sagging in the skin, for example, may be different on the back, belly, rear, or neck.

We make every effort to use the best-looking parts of the hide, but because leather is a living material, we never want to waste anything.